Living in a Time of Climate Chaos Essays

The following are a series of essays penned by Allen Edwards to go with the Climate Chaos seminars he facilitated at SFUU in the Fall of 2019. Other recommended readings include:

online writing/interviews by Jem Bendel

current writings of Naomi Klein.

The Sad Truth About Our Boldest Climate Target by David Roberts

Click on the titles below to go directly to the essay of your choice:

Essay #1: Where We are Now (click here for a pdf version)

Introduction

This essay is the first in a series of background papers for those who wish to participate in the seminar series “Living in a Time of Climate Chaos.” This first paper is intended to explain the reason for the seminars, and put participants on the same page in terms of the latest climate change science and the political and societal response.

Anthropogenic climate change and its consequences are already visiting parts of the globe and are expected to intensify as the world moves through this century and beyond. There is also an increasing perception that the physical manifestations of climate change are likely to result in extensive social disruptions. Parts of the world are already experiencing droughts, storms, wildfires, and heat waves that are exacerbated by climate change. We are already seeing climate induced migrations in the Middle East, South Asia, Central America, and elsewhere and the world's current 69 million refugees have caused significant political stress in Europe, North America, South Asia. It is terrifying to contemplate the political turmoil when the number of refugees fleeing from ocean and riverine flooding, protracted famine, and other climate change impacts climbs into the hundreds of millions or more.

But it is hard to imagine that the full citizenry of the US and other industrialized countries will simply accept the seemingly draconian measures that are necessary if the world goes beyond gestures and promises, and actually works at arresting the warming. At least in the US, some political factions have already threatened to fight climate-related regulations with physical violence. It is a fair guess that the nation's climate deniers, and even many of the climate avoiders, would actively resist an aggressive program to arrest climate change.

And so, regardless of the direction we take, the world faces the real possibility of increasing climate change induced chaos. But how then should we prepare? How do we respond as individuals – as members of the consumer culture that is caused this situation, what are our personal moral obligations to help minimize the ongoing warming, and to make amends for the damage we have caused? How do we protect our families and communities from impending social chaos? And on a broader scale, how can we bring together the currently divided elements of our society to both mitigate the warming and at the same time adapt to it?

These are just a few of the climate-change related questions that call-out for exploration, and that is the purpose of these seminars. There is little expectation these discussions will “find” solutions. But we need a safe place where we can begin open and honest conversations. It is my hope these seminars can offer that.

The Current Best Information on Climate Science

Sign carried in the Sept 20, 2019 Youth Climate Strike in Sacramento

I realize that you all are, to one degree or another, interested in and have followed the climate change issue – otherwise you wouldn't be reading this. Still, I want to start by summarizing the latest and best information I have on climate science just so we're on the same page. In addition to this reading, I encourage you to check my references and other climate science sources listed at the end of the essay.

If major impacts by the turn of the century: the worlds keeps with current trends on climate emissions, we can expect the following:

Average temperatures will rise by as much as 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees F) or more. Parts of the globe will become too hot for human habitation, other parts will become either too dry or flooded.

Scientists expect routine Mega-droughts (extreme droughts that last more than 20 years) around the Mediterranean, parts of Africa, South Asia, South and Central America, and across the western US.[i] [ii] [iii] [iv]

Around the globe, Climate change has already doubled the area wildfires burn. Studies indicate that for every degree C the temperature increases, wildfire median area burned will increase by 200 to 400%.[vi]

If we continue current trends, the sea level could rise 5 feet by 2100 and eventually by 30 feet or more. And there's a chance we're committing to melting all the globe's ice, raising sea level by 220 feet. In any event, our coastal cities will flood, along with our great river deltas and any low lying coastal plains and river valleys. At the same time, the higher temperatures will cause more intense weather, increasing the damage from cyclonic storms and inland flooding.[vii]

Because of the warming, what were once tropical diseases are spreading northward, leaving open the possibility that malaria, dengue, yellow fever, hemorrhagic fever, and others will migrate North, and come to us. [viii] [ix]

The world already has 69 million refugees. The drought, flooding, famine, and epidemics we expect will cause hundreds of millions more. The Syrian Civil war and the Central American Drought – in part triggered by a climate change – are small case studies of the political disruptions an influx of refugees can cause as they move into Europe, or North America, or South Asia, or elsewhere.[x]

And finally there's Famine: each degree Celsius rise in seasonal temperature is expected to reduce global yields of rice, wheat, corn and barley by 2.5 to 16%. Considering all the other warming related impacts, the world could face a loss of half its food production by 2100. At the same time, the United Nations is projecting we'll have 45% more people to feed (over 11 billion). Just stop for a moment and think about how those numbers tragically collide.[xi][xii] [xiii]

This is a sampling of the major impacts. A thorough review of climate change research will reveal thousands of local, regional, and global impacts.

The Global and National Response

How has the world responded to climate change? Scientists have certainly have studied the problem – the points I summarized above are from over 4 decades of intensive research. Our climatologists and biologists and economists have given us more than enough information to justify radical, even fanatical action. So what, then, has the world done?

Internationally, the United Nations has been investigating climate change for 35 years. Because of their program, we have a good idea of where the world needs to go. Last Fall the United Nations climate program told us that, in order to minimize the warming damage to an arbitrary definition of 'acceptable', the world needs to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, and to zero by 2050.[xiv] That means cutting our personal emissions to 3 tones CO2e per person per year – half the world's current per-capita average and one-sixth the US average.

In addition, the United Nations has spent over 25 years developing a framework for international action. This has resulted in worthy goals, widespread mutual promises, but no enforceable commitments.

Nationally we have a different picture. The Republicans accepted the reality of climate change in the 1990s and early 2000s. But the fossil fuels and companion industries undertook a multi-billion dollar campaign of climate change misinformation, while at the same time they lobbied the federal government to block climate change action. [xv] [xvi] As a result, their political clients – some Democrats and almost the entirety of the Republican party – became stalwart climate change deniers. In fact, denial has become one of the litmus tests for Republican party membership.

Other Democrats have offered flashy but inconsequential legislative proposals – the 2009 Senate cap and trade proposal is a good example – then failed to pass most of them. They enacted some minimal administrative programs, but the Republicans recently dismantled most of those, along with blocking any further action. If you've followed this at all, you know the gory details. Today we have a climate denier president and a Republican party dedicated to blocking any climate action. The way we are heading, we will see no meaningful national government climate efforts for 2 years, or 4, or 6, or more. And if the Democrats take the White House in 2020 we may see more of the weak gestures we saw in the Clinton and Obama administrations, but sadly we can't expect meaningful action.

California's government (along with some other state governments) is a brighter spot. The state has a modest cap-and-trade experiment, a program to encourage carbon sequestration, and a scattering of other climate actions. But even here there is a great reluctance to ask citizens to do anything themselves about climate change. And without that, our state will pick the low-hanging fruit, and then what?

What are environmental advocates saying we should do? Ironically, they ask us to turn to government. Some propose a carbon tax, hoping the magic of consumer market forces will convince us to make responsible purchase decisions in light of climate change. Others propose cap-and-trade programs, hoping that the magic of producer economics will make those decisions for us. And still others (recently including the US Chamber of Commerce) would have the government promote technology development – depending on some technologies that are already commercial, and others that are hoped-for miracles.

These proposed solutions have been around for decades. They all have four basic attributes in common: First, they ignore the fact that previous attempts to implement these kinds of policies have failed.

Second, they seek to arrest the warming without having the courage to ask us to change how we live – essentially without really changing anything.

Third, despite acknowledging the spectacular costs shifting to a fossil free society, the proposals ignore what once was a core principle for renewable technology development -- the more we shrink our individual energy footprints, the less money is needed for investment in technology change-over. Unfortunately, they pay only lip service to significantly reducing the energy (and closely related material) demands of the economy.

Fourth, they ask us to trust the power of our government's economic policy, and even more, rely on the very system economic system that brought us climate change, to save us from climate change.Against all basic reason, we are asked to trust this same system with our lives and the lives of our descendants, along with the life of the planet as we know it.

The global youth movement is, in some senses, a breath of fresh air. Leaders like Greta Thunberg are blunt in demanding that our politicians take climate change seriously. They have organized demonstrations and student strikes around the globe in an attempt to raise awareness to some critical threshold. Thunberg in particular is not offering specific proposals on how to fix the problem. Rather, she, a teenager, is asking us to act like the adults we claim to be – calling on the better angels of our nature to well up and respond to the climate crisis. These youth are asking us to take real steps to arrest the warming.

And how have we been responding?Well, I guess we've been trying.If we look at the problem in any depth, we see that it is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, and we surely know that Americans have among the highest emissions in the world.So we must realize that we, personally, are causing the problem.And when we add that to the impacts we know are coming – the ones I described when I started – we, to one degree or another, we certainly feel some moral obligation to do something, don't we?

So we've been trying, some of us anyway. We've taken to heart the widespread advise that we need to start with small steps, because at least they move us in the right direction. Many of us bought hybrid autos; some us stacked solar panels on our roofs; we've offset our air travel and changed our light bulbs, recycle our trash, worked to use fewer plastic bags.

Has all this solved the problem, or just diminished our guilt?The naked truth is that national and global greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow.That's because neither government policies nor our collective actions have touched the root of the problem.And it's become clear that small steps are no longer sufficient. But what should we do?

What Should We Do?

We are facing a time unlike the world has ever seen. Anthropogenic climate change shambles along, dragging us toward a ruin that may ultimately threaten our existence as a species. We know our collective culture needs to stop the warming, or it will surely tear itself apart. But is that even possible?

I've studied climate change science and climate action for more than three decades. I've examined my own guilt as one who is a part the problem. And after all that, I've come to the firm conviction that I and many other Americans may have wanted to stop climate change, but we simply didn't know what to do. We as individuals were waiting something monumental on climate change. We were waiting for an inspiration that would speak to our inner morality, We were waiting for a coherent course of action that makes a genuine contribution to stopping the warming, no matter how small. And we as a part of a political body, were waiting for leadership – not more political rhetoric, but true leadership, proven through example, that would give our communities and politicians the courage to support the values we express.

I believe now we have waited too long.

Over the past few months I have had occasion to reexamine the climate change research I've collected over the past 30 years. I've paid particular attention to information that's emerged in the last few years. Putting all this together, I've come to a sad Epiphany.

I now believe that the world is on the brink of a cascading series of climate tipping points. For example, if arctic sea ice significantly shrinks (as it is doing), the change in albedo will increase arctic warming. That increase will, in turn, increase both arctic terrestrial permafrost melting and melting arctic ocean methane hydrates which will release both carbon dioxide, and methane – a greenhouse gas that is 20 to 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide depending on the time scale. When the first set of these positive climate feedbacks is triggered, the resultant increase in global warming is expected induce other feedbacks – more rapid die-off in the boreal and Amazonian forests for example -- which would further add to atmospheric CO2; and on and on.

Some climate researchers believe we have physically committed to a level of warming that will trigger this cascade of tipping points, others believe we have some time – perhaps a decade or so – to institute a radical program of climate action that could turn us away from the tipping points.

I don't have the qualifications to make scientific judgments. But after 30 years of observing the political and cultural response to climate change, I believe with a high level of certainty that our society will not institute social and political programs sufficient to the need – we will not cut our emissions in half within the next 5 to 10 years, and not cut to zero within the next 20 to 30. And so I believe we have effectively committed to the cascade of tipping points that will inevitably take us to a world 5 degrees Celsius hotter or more.

And so that brings again to the question of what do we do. Despite my years of studying climate change, I don't have an answer. Once I felt the key to arresting climate change was a collective moral uprising of individuals that would force politicians to do the right thing. That hasn't worked out, so now I'm in a quandary.

The best I can offer is that we need to start with a recognition that climate chaos is coming, and then explore what that means.Maybe this will help us discover personal ways of coping with the times we are facing.And maybe, if our collective thinking is powerful enough, we can tease out concepts that reach further – into our communities and beyond.

I hope you will join me in the discussions. I expect within the next few weeks to add to this essay with pieces on: What climate chaos might mean for America and the World, Guilt and Avoidance in a time of Climate Chaos, How to Live in Climate Chaotic World (likely a series of essays on personal economics, ethics, lifestyles, etc), and possibly more. I will post these works on this SFUU social justice web page, and on my website: https://climateunderground.net.

Allen Edwards

i. “How the World Passed a Carbon Threshold and Why it Matters”, by Nicola Jones, Yale Environment 360, January 26, 2017.

ii. “Relative impacts of mitigation , temperature, and precipitation on 21st century mega-drought risk in the American Southwest,” Toby R Ault and others, Science Advances, October 5, 2016.

iii. IPCC AR5 WGI: Climate Change 2013: the physical science basis, by T.F. Stocker and others

iv. Turn Down the Heat, The World Bank and the Potsdam Institute, June 2013.

v. “Climate change in Central and South America: Recent trends, Future Projections, and Impacts on Regional Agriculture.” Jose A Marengo and others, Working Paper # 17, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture, Agriculture and Food security, 2014.

vi. Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and impacts over Decades to Millennia, National Research Council, 2011.

vii. Skeptical Scientist website, Center For Migration Studies, March, 2019.

viii. Climate Change and Infectious Diseases,” JA Patz and others, World health Organization.

ix. “Climate Change affecting incidence of infectious diseases,” AAP News, Sept 27, 2018.

x. “Climate Change, Migration, and the Incredibly Complicated Task of Influencing Policy” Elizabeth Ferris, July 2015,

xi. “Historical Warnings of Future Food Insecurity with Unprecedented Seasonal Heat,” David Battisti and Rosamond Naylor, Science, 9 January 2009.

xii. “Temperature increases reduces global yields of global crops in four independent estimates,” Chuang Zhao and others, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, August 29, 2017.

xiii. “5 ways the world will look dramatically different in 2100”, Ann Swanson, Washington Post, August 17, 2015.

xiv. “Only 11 Years Left to Prevent Irreversible Damage from Climate Change,” Maria Fernanda, Espinosa Garces – speaker of the UN General Assembly, March 29, 2019.

xv. “The Climate Denial Machine: How The Fossil Fuels Industry Blocks Climate Action, The Climate Reality Project, September 5, 2019.

xvi. “Fossil Fuel Interests Have Outspent Environmental Advocates 10:1 on climate lobbying

Essay #2: What Climate Chaos Might Look Like (click here for a pdf version)

Introduction:

I am not advocating climate chaos. Instead, I'm trying to make the case that as we progress into a time of climate change, chaos is likely to come.

This is the second essay in a series intended as background reading for the seminar series, “Living in a Time of Climate Chaos,” which will start Saturday October 26, from 2:00 to 4:00 PM at the Sierra Foothills Unitarian Universalist church in Auburn, CA.

This essay is intended to present information related to why anthropogenic climate change might, along with other factors, lead us into a time of social chaos. I want to make it clear that I am not presenting exact predictions, but rather examples of trends. In fact, any specific scenarios described here are almost guaranteed to be wrong. Never-the-less, I believe the descriptions of trends are sound.

I also want to make it clear this presentation is not comprehensive – this is a brief sketch; a thorough examination would require a year or more and involve hundreds of pages of description. I have also tried my best to filter out hysteria and hype. I must admit however there was no way of making this information upbeat.

You will notice that at the end of each specific area of climate change related impacts, I have have offered a Chaos Quotient – a summary of the those impacts that could disrupt social order. This is for your convenience as you read through this work and as we ultimately discuss the subject. It is important to keep in mind that there will almost surely be synergy among the many impact areas (and in relation to background factors listed immediately below) that would make social chaos more likely than would any single stressor.

What would social chaos look like:

This essay is not an exploration of either social order or chaos itself. Rather, it is a summary of how climate change impacts may push society toward chaos. But what is social chaos?

I could simply say it's when society as we know it no longer provides for our needs. We'll know it when we see it, but until then it's hard to describe. But that is not sufficient.

The chaos I'm talking about would include some or all of the following specific conditions: Certainly the institutions that bring us the our goods and services will to some degree break down. These would include systems that provide food, health-care, utilities, various consumer goods, utilities, transportation, and communication. I'm not necessarily predicting these systems would disappear, but their functioning would be impaired.

A society in chaos would mean the world around us would be in flux, with less dependability in the factors that make up our everyday life. It would likely mean a breakdown in community (political) discourse and decision-making, and certainly an erosion of community services.

There may be changes in the application of power and authority (as now expresses by the rule of law) – either their erosion, or their abuse. With that may come the breakdown social honor, which would result in an erosion of spontaneous social order.

Ultimately, perhaps ultimately most important would be an overall loss of the hope of attainment – the loss of hope in our future.

There are many examples of social chaos readers can study. Certainly some degree of chaos follows most disasters. Some people do rise to the occasion and help their neighbors (and often strangers). Others sink to the occasion and loot from them.

On a broader and deeper scale, we can look at Beirut, or Sarajevo during the Bosnian war, or Syria in the current civil war. Each of these were centers of culture and economic success; each descended into deep chaos in a matter of months or years. I believe the lesson in these examples is that our past economic success and social cohesion does not immunize us from social chaos – it can happen here.

Background factors that already push our society toward chaos:

Before I dive into describing the social, economic, and political stresses that might come from the climate crisis – either from the physical impacts or from efforts to prevent the them – I want briefly touch on a backdrop of pre-existing social flaws, brittleness, and stressors in our economy and society. These, in combination with climate change stressors, would tend to accelerate a move toward social chaos.

A thorough exploration of these would take volumes, so I have simply listed them below so we can keep them in mind as we explore climate change induced chaos. And please remember that the factors below are dynamic – some are more important at some points in time, others at other points.

•Underlying social and economic flaws

◦ political divisions and derisiveness

◦ wealth gap

◦ racial divides

◦ religious divisions

• Brittleness in the system

◦ heavy dependence on fossil fuels

◦ heavy dependence on tech

◦ heavy reliance on high-tech communications

◦ high reliance on fossil-fuel powered transportation – in business & commerce, and in personal lifestyles

◦ heavy dependence on fossil-fuel powered electricity generation

•Potential stressors

◦ Climate change (described below)

• the physical impacts

• aftermath of climate policies

◦ Political disruption (eg, decisive presidential election and its aftermath)

◦ terrorism

◦ War – foreign or domestic

◦ pandemic

◦ famine

◦ religious conflict (probably couched as political conflict, or visa versa)

◦ racial conflict

◦ economic recession/depression

◦ a national default

Potential stressors from climate change impacts:

Heat

If current emission trends continue, global average temperature could increase as much as three degrees C (5 degrees F) by 2050 and 5 degrees C or more by 2100. In addition, with climate change comes increasing weather variability – the low and particularly the high temps will vary more widely from the average than the do now.

In our region, the Sacramento valley and foothill/mountains, highs could increase by 10 degrees F or more during this century. People's ability to cope with these high temps will depend on their location and income. The well-heeled and/or those living in the mountains may do OK, whereas the poor in the valley may not be able to afford the cost of increased air conditioning.

If this is the case, we may see a whole economic class that become “heat refugees” and require extensive heat related social service. The higher heat may also increase electricity rates for those who still need to buy from utility companies (those who couldn't afford to buy their own solar power systems). Ultimately, many may need to move.

The higher heat temperatures will limit the availability of locally grown fruits and vegetables (including those from home gardens). They will also affect local ecosystems, requiring the flora and fauna within them to them northward and up-slope (into the mountains) or die. For example, the lowest altitude of tenability for conifer forests in the Sierras is expected to shift up-slope 500 feet in elevation for every degree C the climate warms. Unfortunately, individual conifer trees and many of their forest companion plants don't migrate. They will die.

Finally, the warmer temperatures will mean less of our mountain precipitation will fall as snow and more as rain. In addition to affecting the ski industry, this will reduce the amount of precipitation stored as winter snow-pack. This in turn, will mean more riverine flooding in the wet season and less water available for agricultural and urban uses in the dry season.

The basic warming described above will also happen nationally and globally. True, the average temperature increases will be somewhat less in the tropics and considerably more near the poles, but the average temperature increases for this region will be about the global average.

Nationally we can expect thousands, perhaps eventually millions of heat refugees. The stress of these folks on social service organizations will be extensive. Internationally, whole regions may become uninhabitable, at least during the summer. The people who currently live there will need to either move or die – potentially leading to substantial numbers of global heat refugees.

Agricultural experts expect the increased heat will reduce food crop production in the tropics and lower temperate areas. Northern latitudes may become more tenable for agriculture if the soils are appropriate, the requisite infrastructure investments can be made, and weather variability doesn't become too extreme (On balance, the Ag. Folks expect food production to drop due to increasing heat – see the section on food below).

Nationally and globally, ecosystems will need to shift northward to accommodate the warming climate. That said, it is difficult to see whole forests shifting hundreds of miles north in the span of a few decades.

The Chaos Quotient:

• more heat refugees

• more need for heat-wave related social services

• loss of habitat from heat related ecosystem shifts

• economic implications of the above

Mega-droughts

Climate forecasters believe there is an 80% chance that mega-droughts (severe droughts that lasts for twenty years or more) will hit the western US between the years 2050 and 2099. (“A 'Mega-drought' will grip the US in the coming decades, NASA researcher says,” Darryl Fears, Washington Post, Feb. 12, 2015.)

For perspective on impacts, the drought in Syria that, in part, led to its civil war lasted from 2006 to 2010. The California drought that led to the death over a hundred million pine trees lasted from 2011 to 2015. If these four-year droughts had dramatic impacts, consider what a twenty or thirty year drought would do.

Certainly it would lead to spectacular ecosystem die-offs particularly perennial plants and the animals that depend on them. Agricultural production would decline – at its peak, California's four year drought idled over a half-million acres of irrigated acres. That drought also reduced regional economic activity almost $3 billion a year.

The California drought did cut into urban water supplies, but a better example of this impact is in Cape Town, South Africa. There, an extended drought took the city to within three months of Zero day – the day when the taps would have run dry. Although some rain has returned, Cape Town citizens are still restricted to 50 liters (13 gallons) of water per day for all their personal needs. Their drought was also four years long.

An example of more extreme drought impacts is the 2010 to 2012 drought in Somalia, which killed 260,000 people. And the Syrian civil war, initiated because of the government's poor reaction to a severe drought, has torn the country apart, created over 13 million internal and external refugees, and killed as many as 560,000 people.

For a broader perspective, 1.4 million Americans and 1.1 billion people globally are currently water-stressed. These numbers will increase dramatically from mega-droughts. The Water Footprint Network predicts that by 2050, nearly five Billion will be water stressed.

The Chaos Quotient:

• more refugees

• less food production

• drought related loss of ecosystems

• possible return of “dust bowl” conditions

• impaired transportation on great rivers

• economic implications of the above

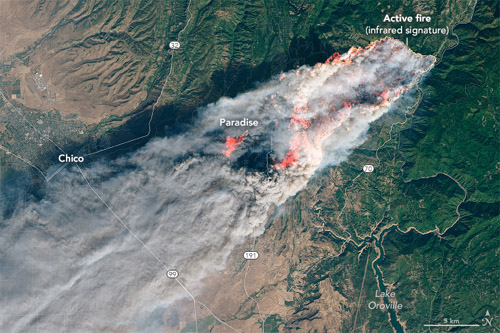

November 8, 2018 Landsat 8 image of the Campfire that consumed Paradise, CA. Image courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory

Wildfires

In California, wildfires are the most potent of possible local natural disasters (if it's fair to call largely human caused and climate-change enhanced wildfires natural). With climate change, the problem is getting worse. The acreage within the state burned by wildfires has doubled in the past half-century.

Last year, California wildfires burned almost 2 million acres (out of a total of 105 million), destroyed 22,751 buildings, and killed 103 people. In 2017, the latest year for which full data is available, wildfires cost the California economy at least 18 billion dollars, including 1.8 billion in suppression costs. (Note the insurance losses on a single 2018 fire – the Camp Fire – exceeded $12 billion).

For us here in the Sierra foothills, the wildfire threat is huge, and it's growing. Research tells us that wildfire median area burned (in California and elsewhere) will increase 200 to 400 percent for every degree C the average temperature increases.[i] When they burn our forests, they burn our houses, sear our landscapes, and scar our hearts.

Globally, attention is now rightfully focused on burning in tropical forests, with special attention to Amazonia, which makes up an important part of the “lungs of the world” – producing more than 20 percent of the our oxygen. The continued destruction of the Amazon forests pushes the region toward a threshold beyond which the viability of that whole ecosystem is at risk, potentially shifting the current tropical forest to tropical Savannah.

Equally important is the huge northern boreal forest. This stretches across northern North America, Europe, and Asia. Wildfires are also intensifying there, and huge fires have burned in Alaska and Northern Canada and Siberia during the past few years. In 2015, for example, 70 million acres of forest burned in Siberia.

These forests, which were historically net carbon sinks (storage areas) have now become net carbon sources to the atmosphere. Even worse is the fact that many of the fires are burning deep in to the legacy CO2 stored in the soils. In addition to the greenhouse gas emissions, these fires are changing Arctic hydrology and weather cycles.

We should also not forget that climate change is causing an increased wildfire damage in other Mediterranean climates around the world – southern Europe, the Middle East, Australia are just a few of the regions affected. Like here, the people of those areas fear for their property and lives, and suffer tremendous losses due to the growing wildfire risk.

The Chaos Quotient:

• direct injury, death, and damage from the increasing fires

• increasing wildfire refugees

• damage and disruption to utility, transportation, housing infrastructure (and the possible permanent abandonment of infrastructure in some areas.

• Increased lumber prices (from loss of forests)

• increased insurance costs (and the possible loss of coverage in some areas)

Flooding:

As our climate warms, the snow-line in the mountains will rise, and more of our local precipitation will fall as rain. As a result, rather than being stored in the mountain snow-pack, precipitation will run directly down into our rivers. At the same time, climatologists expect more “atmospheric river” type warm storms to visit California. This combination is expected to lead to more flooding in Northern California's rivers and creeks.

In the Sacramento delta and valley, this flooding may be intensified as ocean level rises push tidewaters further inland, particularly if storm-related tide surges coincided with heavy, warm storms. Parts of the delta, and possibly even neighborhoods in Sacramento will be at risk.

The river and creek flooding projected in our local area is also expected in watersheds around the world. Recent floods in the Mississippi, Indus, and Ganges rivers are mild examples of what's to come.

Scientists expect sea level to rise 3 to 6 feet by the end of the century. Recent paleo-climate analysis shows that during the Pliocene epic (three million years ago), when the atmospheric CO2 levels were 400 parts per million (they are now over 410) the ocean temperature was 2 degrees C higher and the ocean was 65 feet higher. [ii] If this history is relevant for our future, large parts of San Francisco and the Sacramento valley are almost certain to eventually flood.

And as the ocean level rises, all of the world's coastal cities, great deltas, and lowland agricultural valley's will be subject to permanent flooding. The people who live, farm, and manufacture there will need to move or drown. And the great shipping ports – a key component of the world's oceanic transportation system, will need to be moved or protected. Disruptions of their operations will surely occur.

The Chaos Quotient:

• more creek and river flooding

• more storm related damage to dams, levies, and other elements of our water infrastructure (eg the 2017 Orville Dam failure)

• Intensified delta and valley flooding from rising ocean levels. (Note: the tides already cause a 3 foot fluctuation of river levels in Sacramento.)

• chronic flooding around the world from ocean level rise

• disruption of global shipping

• hundreds of millions of refugees

• expect economic impacts in the $ Trillions, for example:

◦ billions in damage from the 2019 Midwest flooding

◦ natural disasters (mostly storm related) cost the US economy $307 billion in 2017.

• Sea level rise could cost the world $14 Trillion by 2100 [iii]

Disease:

The global tropics are home to some of the most intractable diseases know to humanity. Chagas, Dengue, Sleeping Sickness, Malaria, Hemorrhagic Fevers, and others diseases have plagued people in the worlds tropical areas for time immoral. Just one example – it has been estimated that mosquito-borne illness has killed half the people who have ever lived.[iv]

Fortunately, in the past century, public health efforts have reduced the impact of some of these diseases, particularly in the southern US. There are vaccinations that impart immunity for some. But they are still huge health problems. According to World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 there were 219 million cases of Malaria in 87 countries, which resulted in 435,000 deaths. And again, according WHO, there have been 17 outbreaks of Ebola Hemorrhagic fever since 2000.

These diseases are devastating to the victims, and to the economics where they appear. The global economic cost of Malaria is estimated at 12 Billion per year. The Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2013 to 2016 killed at least 11,300 people and cost an estimated $52 Billion (“West Africa's Ebola outbreak cost $53 Billion,” Tom Miles, Reuters). That epidemic virtually shut down the countries of Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia for months. Fortunately, except for isolated cases, an international effort prevented prevented the disease from spreading beyond West Africa.

But many of these diseases are expected to spread northward with climate change despite best efforts to contain them. The range of Aedes Aegupti, the mosquitoes that carry Dengue fever, Zika virus, Chkunyunga, and Yellow Fever is currently restricted to the tropics, with short seasonal intrusions (a few months each year) into the Southern parts of California, Arizona, and New Mexico. By 2080,under business as usual warming, it will spread over most of North America, as well as Northern Europe and Asia. And in California, it will be present for half the year in the Central Valley and foothills. (“How does climate change affect disease,” Stanford University – Stanford Earth).

Other species of disease carrying vectors – other species of mosquitoes, flies, ticks, etc. are also expected to spread north with the warmer weather. Good public health can protect us against some of the disease they carry, but our vulnerability will, even in the best of times, will increase. And we won't be facing the best of times.

Finally, in addition to human diseases, climate change may increase the incidence and severity of plant disease problems both in tropical and temperate parts of the world, which will affect global food production.[v]

The Chaos Quotient:

• increased local sickness and death from once tropical diseases

• vastly increased stress on local health-care systems

• increase in refugees trying to escape pandemic areas

• growing economic costs of health care, particularly in lower latitude temperate regions (California, Southern Europe, South Asia, far north and far south Africa, Australia, and parts of South America).

• Increased social and economic disruptions from epidemics

Food

While there are local farms that supply food to our local markets, and the nearby Sacramento Valley produces a plethora of vegetables, fruits, and nuts, most of us get our food from the global food chain through our plentiful supermarkets. Thus, here I will focus on global food supplies.

Four of the areas discussed above, heat, mega-drought, flooding, and disease; while significant impacts on their own, will in turn affect food production.

Heat waves will reduce production, if they don't kill crops outright. At some stage of warming, they will render agriculture untenable in some areas.

The UN's Food and Agriculture agency estimates that 36 percent of the world's total food harvest comes from irrigated land. Droughts will of course reduce the water available for those crops. But they will also reduce, drastically in some cases, harvests from dry-land agriculture.

Riverine flooding not only kills people, it devastates crops and cropland. The 2010 floods on the Indus river killed 1500 people and affected 20 million more. But the flooding also destroyed 700,000 acres of cotton, 200,000 acres each of rice and cane, 500,000 tonnes of wheat, 300,000 of animal fodder. [vi]

And rising ocean levels will flood all of the world's major agricultural deltas – the Indus, Ganges, Nile, Mississippi, Niger, and many more (including the Sacramento). It will flood up the low-lying agricultural valleys, turning them into bays and estuaries.

Plant diseases already reduce global food production by 30 percent (FAO). Climate-change induced plant diseases are expected to intensify in the tropics and spread across temperate agriculture.

Finally, the increase in weather variability expected from climate change – both the precipitation variability and the temperature variability – is expected to cause ongoing disruptions to agricultural operations around the world.

Adding all these impacts, scientists estimate that for every one degree C rise in temperature, global food production will drop by 5 to 15 percent (National Academy of Science, 2011). Current trends are expected to raise global temperatures 3 degrees C by 2050 and 5 or more degrees by 2100. This computes to the possibility that global food production could fall almost 50% by mid-century.

The Chaos Quotient:

• more food refugees (like those already coming out of central America)

• increased food prices, along with shortages of some products

• increasing overall food shortages, initially affecting the poor and increasingly affecting all of us.

• Surprise food disruptions (caused by droughts, disease outbreaks, heat waves, floods)

Refugees

All six impact categories describe above will result in increases in refugees – people fleeing the impacts of climate change. The International Organization for Migration projects between 25 million and 1.5 Billion climate refugees by 2050. the UN International Organization for Migration estimates 25 million to One billion for the same time-frame.

Where will all these people go? How will they live? How will they house, cloth, feed themselves after they have been driven away from their homes?

The current refugee crisis in Europe has been triggered by approximately a million people fleeing there because of the Syrian civil war. The US immigrant crisis, though arguably intensified by political manipulations, is about the immigration of less than a million people a year.

Imagine the social and political upheld from ten million, or a hundred million, or more. Will we lift our lamp and shelter these tired, poor masses? Or will we drive them away? This is a crucial ethical question given that we, through our emission of greenhouse gases, are causing the conditions that will have led to their dislocation.

The Chaos Quotient:

• economic, political, and social disruption from millions of refugees entering California, the US, and other developed countries.

Aggregating the economic impacts:

Every local climate-caused crisis will hit our local economy. Heat-waves can disrupt school and civic schedules, as well as business and commerce. Major wildfires can disrupt the operation of health-care facilities, local business and commerce, cause massive local housing shortages, and on and on (the 2018 Camp Fire is a good example). Local and regional flooding can disrupt transportation, as well as housing, business and commerce. As an example, the cost of natural disasters in the US in 2017 totaled $306 Billion (NOAA, 2018) – most of these costs falling on local economies. And they will grow exponentially as climate change progresses.

More broadly, extreme weather has cost the US economy 1.6 trillion dollars since 1980. Looking ahead, a 4 degree C rise in global temp by 2100 would cause the global economy to decline more than 30% from 2010 levels – worse than the great depression of the 1930s, when global trade fell by 25%. [vii] And don't expect that the US economic wealthy will mean that we will avoid the economic costs of climate change – analysis shows that the economic cost in the US will be among the highest in the world. [viii] [ix]

And its important to keep in mind that these numbers assume that climate-caused caused economic decline will be orderly – perhaps a heroic assumption, particularly since both nationally and globally, climate change will increase both social and economic inequity. The rich can vastly more easily move their productive assets and their households to more climate-friendly areas than the poor, but the poor and near poor will surely respond.

Aggregating the Chaos stressors from climate damage:

I want to try to encapsulate the information above. If climate change progresses on its current trajectory, our local area and the broader world will be hit by acute crises – heatwaves, conflagration wildfires, major storm events, with both riverine and coastal flooding, pandemics; chronic crises – droughts, famine, endemic diseases, incremental ocean-level rise, influx of locally generated and foreign refugees, and climate-related economic decline.

Potential stressors from a response to government climate policies:

I want to change gears and explore what might happen if humanity took the warnings from science on climate change serious. The catalog of impacts above is based on the assumption that national and international government actions will not be sufficient to prevent our climate from tipping into catastrophic climate change. I think this will be the most likely situation, but still, it is worth examining the stressors that might hit us if governments did enact policies that were effective in preventing outright climate collapse.

Based on the best available science, the world needs to arrest the warming at 1.5 degrees C or below in order to keep us from falling into a cascades of climate tipping points that would take us to 5 degrees C or higher (see essay 1 of this series for a fuller explanation of tipping points).

Achieving that – keeping the warming below 1.5 degrees – would require humans to cut our greenhouse gas emissions in half within the next 5 to 10 years and to zero within the next 10 to 20.

Setting aside the political difficulties (perhaps impossibilities), what would happen in this country if government policies that would actually achieve this were instituted?

Forty-two countries already have carbon taxes, or equivalent cap-and-trade programs, that price carbon dioxide emissions an average of $8 per ton. But there has been severe backlash in some of these countries. Australians reacted fiercely to a $23 per ton price. In France, a proposed gasoline tax increase of 6 or 7 cents per liter (about 25 cents per gallon) triggered riots which caused four deaths, 250 injuries, millions of dollars in damages.

In the US, conservative think-tanks have spewed out climate denial misinformation on climate change for three decades. Conservative commentators argue that the entire climate issue is a conspiracy designed as a cover for a Soviet-style liberal/socialist takeover of the government. Conservative politicians parrot the information they receive from these sources.

And apparently many everyday Americans listen to this misinformation. Fifty-eight million deny the reality of climate change. [x] Only 56 % say protecting the environment is a top priority. Fifty-one percent say climate change policies make no difference or do more harm than good.[xi] Finally, only a third of Americans would support an extra tax of $100 dollars a year to fight climate change. [xii]

And yet, last year the UN reported that governments need to impose effective carbon prices of $135 to $5,500 per ton of CO2 in order to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees C. [xiii]

For a bit more perspective, the average American emits about 20 tons CO2 or its equivalent each year. The UN recommendations for avoiding the cascade of climate tipping points would tax each person $2700 to $110,000 per year. This is compared to what most Americans want – no tax or at most a tax limited to $100 a year.

So again, what might happen if our government went through a radical shift and started supporting real action on climate change? What if it adopted a carbon pricing program along the lines of the UN recommendations? How many Americans would accept a tax of $2700/ year, let along taxes orders of magnitude higher? How would they express their objections? A letter writing campaign? (Unlikely, that's what progressives do, not conservative.) Non-violent demonstrations? Maybe some, but how many of the climate deniers are second amendment folks? How long might they stay nonviolent in the face of what they've been convinced is a socialist conspiracy to control their government and their lives?

Parting thoughts:

It's hard to fully grasp the dangers our society faces as we move into the age of climate change. Social undercurrents already present threaten to burst to the surface and spill us into chaotic situations. When we add the all the stressors from climate change, and particularly the opportunities for interaction between our existing social weaknesses and newly imposed climate impacts, it seems hard to imagine that our world will continue to muddle along in its current semi-orderly state.

I think the example of Syria is particularly instructive. A four-year drought and its resulting famine triggered a public response which was poorly handled by an uncaring, authoritarian government. This precipitated into a civil war which, as describe above, killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions. Then a small fraction of those displaced fled to Europe, where their presence destabilized the politics across the whole region.

So in Syria one climate stressor triggered a cascade of impacts that affected a whole continent. And Syria was a minor incident compared to what will come.

All of these are forces we individuals can't stop. And so, I believe we need to come together and figure out how to live in their shadows.

Respectfully, Allen Edwards

i. Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and impacts over Decades to Millennial, National Research Council, 2011.

ii. “Climate change could be hurling earth back to the future, raising sea level by 65 feet,” Georgia Rose Grant and Timothy Naish, Newsweek, 10/3/2019.

iii. Phys Org, Institute of Physics , July3, 2018.

iv. “Mosquitoes may have killed half the people who ever lived,” New Scientist, 7 August 2019

v. “Climate change, crop plant diseases and future food production,” Dr. Jillian Lenne, World Agriculture, July, 2018

vi. “2010 Pakistan floods,” Wikipedia.

vii. “Climate change facts and effect on the economy,” Kimberly Amadeo, The Ballance, Kune 25, 2019.

viii. “Climate change will cost US more in economic damage than any other country but one,” Stacy Morford, Inside Climate News, August 2019

ix. “Climate change will cost US more in economic damage than any other country but one,” Stacy Morford, Inside Climate News, August 2019

x. “Surprise! New pol shows Americans lead the developed world in climate denial, Yessenia /Funes, Earther.Gismodo, 5/8/19.

xi. “How Americans See climate change in 5 charts” Cary Funk and Brian Kennedy, Factank, Pew Research Center, April 19, 2019.

xii. “Americans demand climate action, as long as it doesn't cost much: Reuters poll,” Valerie Volcovici, Reuters, June 26, 2019.

xiii. “New U.N climate report puts a high price on carbon, Brad Plumer, The New York Times, October 8, 2918

Essay #3: Ethics in a Time of Climate Chaos (click here for a pdf version)

More people are now recognizing that climate is an ethical issue. They write, testify, just talk, and sometimes even preach that readjusting our ethical outlook is the key for finding government and business policies that will help arrest the warming. But is that really true.

Ethics has to do with how groups should behave. Ethics drive group policies and their execution, including in government and business. The growing belief is that a focus on climate change ethics will help us get governments policies which encourage or force citizens to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and push corporations to make their operations climate friendly. Maybe.

Future generations will live with the results of our current and past carbon emissions.

But during the last half-year I have come to the sad conclusion that our society won't act sufficiently in arresting the warming before it tips into a cascade of positive feedbacks (secondary impacts from the initial warming that make the problem worse). If I am right, this cascade will take our world into warming-induced chaos despite even the best efforts to change our ethical practices. As a result, I am now focusing on moral behavior – on my behavior and that of others as an individuals, in spite of climate change – as we move into a time of climate chaos. That will be the focus of this essay.

The good news is that focusing on morals sets aside thorny ethical questions related to climate change. Questions like: how much warming is OK; how much do we need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; is coercion acceptable in order to get people to reduce greenhouse emissions, and if so how much; and on and on. These ethical questions may once have been important, but they aren't as relevant if catastrophic climate change is coming regardless.

More important to me then is how I as an individual should act regardless of what comes. But even here, there are a plethora of moral questions we could explore – easily leading to confusing diversions. So I want to narrow the discussion down to a moral essence – to the two crucial questions I believe should drive our behavior as we move into increasing climate chaos.

The human behaviors causing climate change are our consumption of fossil fuels, products and services made with fossil fuels, and other activities driven by our desire to consume more (more meat, more wood, more electronics, and on and on). Consumption is key; and particularly in industrial economies, consumption drives our daily lives. But how does our level and type of consumption fit into a moral framework that relates to climate change? What are the moral questions we need to explore.

The first is: how do we individuals, particularly we who are economically privileged, stop the damage our greenhouse gas emissions are causing? The second: how do we (again we economically privileged) make amends for the damage our past emissions have caused?

Looking at these as moral questions, the emissions of others, the actions of the great energy corporations, and the inaction of our national government are not immediately relevant. Our behavior is the focus.

Looking at these questions from from a theological point of view, Christians, Jews, and Moslems all sign on to a moral code whose summit (at least for Christians) resides in the Ten Commandments. Three of those commandments seem relevant here:

Thou shall not kill – but our behavior, through our greenhouse gas emissions, is contributing to killing hundreds of thousands if not millions of people. As we move through this century and beyond that number will rise – perhaps to hundreds of millions or more.

Thou shall not steal – yet our emission are stealing the stable atmosphere and environments across the globe it supports, causing the misery of tens of millions of people, and will eventually ruin the lives of billions – people living now and those from future generations.

Thou shall not bear false witness – and yet many of us have for years denied the existence of human-caused climate change, or more commonly, denied that we needed to change our lifestyles to stop it. Some of us have advocated a position of outright climate denial; and most of the rest of us, despite the overwhelming evidence that justifies aggressive action, have supported a position of climate avoidance through our lack of meaningful action. So either by assertion or omission, we are publicly denying the importance of climate change and thus are guilty of false witness.

So from a theological point of view, my past and continued emission of greenhouse gases make me guilty of committing three major sins. I suspect most of you readers are in a similar position. And despite our words, we continue to do this daily and so are effectively unrepentant.

A more secular point of view of climate morality would look at crimes rather than sins. Oxford dictionary defines crimes against humanity as “deliberate acts, typically as a part of a systematic campaigns, that causes human suffering or death on a large scale.”

I argue that, given all the readily available information on climate change and its impacts, our continued greenhouse gas emissions is a deliberate act. And by our willing participation in an economy driven by the longstanding campaign of fossil fuels and industrial firms – one that urges us to keep consuming – we are a part of a systematic campaign that results in billions of tons a year of greenhouse gas emissions and is responsible for human tragedy of global warming. As a result, I and many of you are guilty of a secular “crimes against humanity.”

In either case my/our sins/crimes are terrible. I have helped cause the misery of millions if not hundreds of millions, and helped kill hundreds of thousands if not millions. The damage will grow as we move through this century and beyond. Yet for a considerable time I denied the problem and then denied the extent of my contribution.

For all of that, I need to redeem myself. How I do that won't be easy. Even discussing it may be difficult. But I'll introduce concepts in my next essay that I hope will help

Respectfully, Allen Edwards

Essay #4 – Living a moral life in a Time of Climate Chaos (click here for a pdf)

In Essay One of this series, I summarized the latest science on global climate change, and I made my case as to why I think we are committed to a cascade of climate-related tipping points that will warm the globe 4, 5, 6 or more degrees Celsius regardless of how furiously we we try to prevent it.

For review, the greenhouse gases that I (and almost surely you and everyone around you) emit every day are changing our climate and driving growing tragedies around the globe. Already the world is seeing heat waves, droughts, floods, weather extremes, ocean acidification, and other direct climate impacts from our greenhouse gas emissions. These are causing secondary impacts like famine, civil war, conflagration wildfires, waves of refugees, and on and on. These local and regional catastrophes aren't natural events – they are the results of my emissions and those of other consumers.

In Essay Two, I offered a menu of climate change-related stressors I believe will (along with the grave social and economic stressors already coming at us) likely to push us into a time of regional, national, and global chaos.

In Essay Three, I argued that people are suffering and dying because of my emissions, and so I am either committing a sin, or a crime against humanity, or both. I then identified what I believe are the two crucial questions we must explore if we are to live a moral life in a time of climate chaos. For reference through the remainder of this essay, those questions are as follows:

First, how do we stop our personal contribution to global climate change, and all the damage this is visiting on humanity, through our emission of greenhouse gases.

Second, how do we make amends for the damage our personal emissions to date have caused, are causing, and will cause in the future? (Most greenhouse gases remain in the atmosphere for centuries.)

There are, of course, a plethora of other moral questions related to climate change. Giving justice to all of them might be interesting to a theologian or a moralist, but I need to focus on the essence. And I believe that how we answer these two questions will define the broader scope of our moral behavior in the times to come.

A note here: through the remainder of this essay I will use myself as the moral whipping boy – talking about my moral obligations and what I need to do to fulfill them. I hope using myself as an example will facilitate the discussion on moral obligations we all have, not simply convince you that I'm a bad person (which may also be valid).

Moral Question One, then, is about stopping my sin/crime (from now on, I will simply refer to it as a sin). Right now, I'm not concerned about the greenhouse gas emissions of the rest of humanity; and no matter how egregious I'm not concerned about the malfeasance of our politicians or those who run the great oil companies or Joe down the road who drives a Hummer. After all, none of these people forced me to spew greenhouse gases into the atmosphere – this is my responsibility.

So I'm focused on how I can stop my continuing sin of greenhouse gas emissions -- how I can cease the harm my emissions bring to people all around the world. No matter what other great deeds I do through the remainder of my years, if I fail at this I will fail to lead a moral life.

But what does that really mean – stopping the sin of greenhouse gas emissions? Is some lower level of emissions OK, or do I need to cut them to zero? Are some types of greenhouse gas emissions morally acceptable while others are not? And is it OK for me to disrupt the world around me – people, local economy, local community institutions – by eliminating my emissions; or is some compromise of reductions the better path, knowing that my compromises will damage people further out in the world?

I don't have an answer to these questions – this is what I want to explore in the seminars. I will, however, offer an analogy that might illustrate the moral dimensions of this question. Slavery, like climate change, was (still is) a moral issue. It was/is morally abhorrent for people to own other people. And so, while it would have been good for a slave owner with ten slaves to free nine of them, his ownership of the last one was still immoral.

So then, if I'm emitting 20 tons of greenhouse gases a year, cutting 90 percent of them would be good. But the two tons I continue emitting is still causing damage. So is this morally unacceptable? Or have I cut enough?

Also, I believe its fair to recognize the technical difficulties of entirely eliminating my emissions. Maybe the concept of “net zero” emissions – a combination of adding and subtracting greenhouse gases to the atmosphere that results in a net of less than zero staying there – is an important consideration.

And then there is the question of how soon I need to cut my emissions. The United Nations says the world needs to cut emissions in half by 2030 and to zero by 2050. Is that good enough for me, or am I morally obligated to cut my personal emissions as quickly as possible?

My bottom line then, is how much and how soon do I need to reduce my greenhouse gas emissions to fulfill my responsibilities as a moral person?

I want diverge here and settle the question of why I can't simply counter my greenhouse gas emissions with offsets. These are where a person takes greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere to displace the gasses they emit into it. The most common offset method is carbon sequestration – pulling Carbon Dioxide (the most significant greenhouse gas) out of the atmosphere and sequestering it in a permanent state. The most typical current carbon offset is reforestation – planting trees which, as they grow, pull carbon out the air and put it into the wood of their roots, trunks, and limbs.

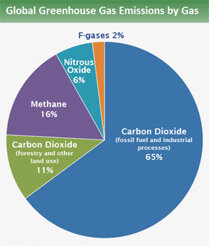

Graphic courtesy of the IPCC (2014) via the EPA (https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data)

There are other greenhouse gases we emit or, cause to be edited through our lifestyles. These include Methane, Nitrous Oxides, a variety of Chlorofluorocarbons, and other industrial gases. All of these are more potent per unit of mass than Carbon Dioxide in terms of their climate change impact, but the glory of offsetting is that any greenhouse gas pulled out of the atmosphere can offset any we emit. We just need to make sure our accounting is good – for example, we would need to pull out 300 kilograms of CO2 for every kilo of Nitrous Oxide we emit because Nitrous Oxide has 300 times the warming effect of CO2.

This seems simple. In my part of the world, a fast growing conifer forest can sequester three tons of carbon per acre per year. And as long as these reestablished forests endure, they sequester a lot of carbon – eventually tens, if not hundreds of tons per acre. So why can't I just pay one of the many companies offering offsets to counter all my current greenhouse gas emissions and then just go on with my life the way they is?

Unfortunately offsets are not always what they appear. Particularly for reforestation, they aren't immediate nor (in an age of conflagration wildfires) permanent. And reforestation should already be happening for many reasons that have nothing to do with climate change. Also, reforestation offsets can be and have been used to justify heavy logging – essentially justifying deforestation by saying that offset reforestation will fix it. And a reforested area sequesters nothing like the carbon its mature predecessor did – not for decades and perhaps centuries.

Forest related offsets, particularly those based in third world countries, can also cause serious problems for the people dependent on those forests – people we don't see and never know when we plunk down our dollars to offset our latest plane trip. And some offset programs are rife with varying degrees of deception (called marketing) or outright fraud. Even more important, relying on offsets does nothing to change the institutional structures that have and are causing greenhouse gas emissions and the resulting climate change.

But most important to me, simply offsetting my greenhouse gas emissions amounts to papering-over my moral failing with a technical fix. In doing this, I would use the money I earned, in part at least, by emitting greenhouse gases to hide my guilt. But my moral dilemma remains.

I will note that there may be a place for what I call personal offsets – ones I do with my own hands preferably on my own land. I hope we can discuss the distinction between those and commercial offsets in one of the seminar sessions.

Moral Question number Two: “How do we make amends for the damage my personal emissions to date have caused, are causing, and will cause in the future? ” is both direct and subtle. I feel a moral obligation to help the people climate change is hurting. I could simply contribute to great disaster relief organizations – Red Cross, Mennonite Central Committee, International Rescue Committee. That's simple – right?

But how do I balance the immediate needs from current disasters with needs coming from slowly evolving tragedies – ones like the chronic famines expected later in the century. Maybe some or all of my contributions should go to organizations like Oxfam or The Heffer Project that help raise the productivity of substance farms?

Then there's the question of how much money should I spend on this? This in turn begs another question – how much of the money and things I now have have I gotten through activities that, directly or indirectly, emitted greenhouse gases? A thorough appraisal of this would be difficult, illuminating, and probably terrifying. Because if some or most of my assets came from sinful (or criminal) activities, am I entitled to them? Or do they need to go to the victims of my sin?

And do I need to explore question two in the context of question one – do I need to make amends in a way that causes no further damage? This would make the whole project more … interesting.

I believe these questions need to be discussed before we delve into the practical world of actually cutting emissions. I wish I had clear and acceptable answers, but then if they came easily we wouldn't be facing the global catastrophe that's now before us.

Respectfully,

Allen Edwards

Essay #5 – Exploring the Possibilities for Reducing Our Climate Footprint (click here for a pdf)

We are each capable of great deeds. But if we stay stuck in the little ruts our current social system, our lives will fade into oblivion.

We are facing a time unlike the world has ever seen. Human-caused climate change shambles along, dragging us toward a ruin that may ultimately threaten our existence as a species. We know our collective culture needs stop the warming, or it will surely tear itself apart. That should be simple – each of us just stops our emission of greenhouse gases, the human caused agents of our crisis. But those emissions are integrally tied to our lifestyles, which are embedded in our culture – tied to the point where it seems impossible for us to change. How can we shift an entire culture if we can't even change ourselves? And if we've waited too long?

Our politicians aren't helping. At best, or worst, they give us words – promises or threats depending on who you follow. They all talk about solutions, while actually they simply work to stay in power. And sadly none have demonstrated they will truly lead us to salvation from climate chaos.

Industry isn't helping either. Some companies make green promises while others give us reams of climate misinformation. With great fanfare they promote coming technological miracles. But when will these arrive will they actually save us or just dig us into a deeper hole. Sadly, while companies might gesture and tinker, they block significant changes because those would drastically lower our consumption and hurt their profitability. Ultimately, industry wants us to continue worshiping the power of the global market – the very same power leading us to climate destruction.

What about our spiritual leaders? Despite the teachings on honesty and service they pretend to champion, some flatly deny the scientific truth of climate change and the human tragedies that follow in its wake. These realities should make greenhouse gas emissions a grave sin. Yet some leaders commit yet another sin – false witness – when they advocate against the truth of climate science.

Other faith leaders are social justice advocates who include climate change in their portfolios, but they face so many needs with so little time. Nevertheless, climate change impacts are growing into the overarching social injustice of our time. Shouldn't this issue be their highest priority? And wouldn't solving this problem also address other injustices as well?

And finally, sadly, many church leaders have simply been silent on climate change. Maybe they are waiting for an Epiphany, but in the meantime disasters spread across the world.

Global annual average temperature has increased by more than 1.2°F (0.7°C) for the period 1986-2016 relative to 1901-1960. Red bars show temperatures that were above the 1901-1960 average, and blue bars indicate temperatures below the average. (right) Surface temperature change (in °F) for the period 1986-2016 relative to 1901-1960. Gray indicates missing data. From Figures 1.2. and 1.3 in Chapter 1 courtesty of the US Global Change Research Program: USGCRP, 2017: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I (https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/csd/assessments/climate/2017/covercitations.html).

Climate change has evolved from a problem on the horizon, to a coming storm, to now an active crisis. We already see its impacts in floods, droughts, famines and conflagration wildfires. Our continued emissions of greenhouse gases has led us to the cusp of a cascade of climate tipping points that will likely warm the planet 4 to 6 degrees Celsius or more, regardless how we respond. The climate catastrophe we could have prevented has arrived.

So for now anyway, we individuals (and our close communities) must respond to climate chaos on our own. But what should we do? Incrementalism – making small changes intended to lead us in the right direction – hasn't worked. Last year global greenhouse gas emissions grew 2.7% and US emissions grew 3.4%. Society is on the track of the worst climate scenarios the scientists can imagine.

We might have tried to sweep across the globe with an ethical movement that rejected consumerism and replaced it with economic and social institutions focused on human sustainability. We didn't; so what now?

We could pull out our personal bucket-list – all the indulgences we've ever imagined – and live petal-to-the-metal until climate chaos strikes us. But if all society takes that course, we will go down in a gory blaze of consumptive excess, dooming most of humanity to destruction and the survivors to enduring misery. Our binge might give us fleeting pleasure, would fail to fulfill our deeper needs, and the hangover would be monstrous.

Or we could keep ignoring the problem, hoping politicians will solve it, or some undiscovered technological miracle will make it go away. These paths take us to the same world of pain without either transient pleasure or abiding fulfillment.

But we can search for a new hope – one that reflects to our inner sense of morality and self-worth; one that works to keep our personal dignity and help us find deep fulfillment as we move into a time of climate chaos. This requires that we examine how we live, and how that affects the world, and decide what we want our relationship with that world to be. If we do all that in light of our moral responsibilities, we will conclude that we need to reset our way of living to one that's consistent with saving what we truly value.

All this goes beyond trivial gestures and promises. Most of us will need to make radical changes in our lives, and these will go far beyond simply shifting from buying one product rather than another; changing from this technology to that one. We need to make deep and enduring changes in our personal lives and our entire social structure.

How Much Should We Reduce Personal Emissions and Reconfigure Our Lives?

The previous four essays in this series presented a summary of current climate science, including climate change impacts. They also offered a moral perspective on the problem, and focused on two key questions: How do we as individuals stop the damage our greenhouse gas emissions are causing? And how do we make amends for the damage caused by our past emissions? There was lengthy discussion on these questions in the companion seminar to these essays. Participants reflected a deep consensus that we have a moral responsibility to both reduce our emissions and make amends.

But the discussion seemed to stall with the twin follow-on questions: How much should we reduce personal emissions? And how do we reconfigure our lives so we can truly make amends.

I've given much thought as to why participants had difficulty answering these latter two question. I conclude that we held back because we can't conceive how we might cut our emissions in half, let alone to zero. We view life within the framework see around us. And so we judge the possibility of change through the lens of that view.

But what if we change the lens. What if we let ourselves imagine other ways of living that aren't constrained by the walls of the competitive society our current industrial economy has sold us. What if we step away and envision other ways of living that are sustainable; that reject the ongoing injustice of climate change; that give us comfort and sustenance and fulfillment and moral peace. What if we take that image of a new life, and shift into it – not with timid, tiny steps, but in a full-throated adventure. I believe if we do that, we might find our way to better lives for ourselves, and a better world for everyone. Just maybe.

I am proposing a paradigm shift in our lifestyle – pulling away from the destructive aspects of the current American dream, and reconstructing our lives in ways that support global justice and sustainability. This could be a thoroughly daunting and confusing effort. So in order to make this easier and more orderly, I propose it be done in five steps. Those who have attended the first seminar session, or read the first four essays in this series, may have already moved through step one as described below – Believe. I would caution,though, that each of these steps is crucial, and each subsequent step builds on the ones before. None of the steps are casual, and those of us working through this need to retain the beliefs we gain from step one as we move into step two – Imagine – and then retain both the belief and the image as we move into step three. And on through the process.

This path will take contemplation, discussion, and ultimately community support. This path takes us completely beyond small incremental steps, and into one giant leap. But after over thirty years of studying climate change and how to stop it, I think this is the only path that takes us to the deep changes we and the world needs.

The five steps in this adventure are as follows:

Step One: Believe – believe the truth about climate change, that we need to respond, and that we can.

I think most folks do not yet understand, let alone fully believe, the scope of climate science and the extent of the changes that are coming at us. Before we can adequately respond as individuals and as a society, we need to believe that climate change threatens our civilization to its core and that it is the overriding social justice issue of our time. And we must believe that we are causing this problem through our ongoing demand for goods and services. And finally, we need to believe that we have a moral obligation to change our lives in response, and that we can change. If we don't truly and fully believe all this, any changes will be inadequate. But with a genuine moral commitment, it will.

Step 2: Imagine – build a new dream to replace the consumer-based American dream.